martes, 24 de noviembre de 2015

Dictionaries

Dictionaries

are similar to list. They can store many values that can be used when called. The

difference between a dictionary and a list is that every value stored in a

dictionary as mapped to another value.

For

creating a dictionary we use the function dict( ). For stating that something

is dictionary we type the name we want to assign to it followed by the equal

sign. After the equal signs, you start typing the values between curly brackets.

For writing a value it is necessary to type the value, a colon, and the value

it is being mapped to. For separating each set of values we use commas.

As you can

see, when you try to print a dictionary, the values inside of it are printed

without an specific order. For example, if you print them again, the order will

be completely different:

Also, you can get the value is being mapped to another value. Also, you can change the value it is being mapped to:

domingo, 22 de noviembre de 2015

Tuples

A tuple is

a sequence of values that are nested into one function. These elements can be

strings, number, and even tuples. You can have many types of elements within

the same tuple, for example:

Colors = (‘red’,

‘blue’, ’yellow’ )

Numbers = (

1, 2, 3 )

List = ( 4,

(5, 6))

Other = ( ‘red’,

2, (5, 6) )

As you can

see, tuples are pretty much like a list; what differentiates them is that

tuples cannot be mutable. For creating a tuple you need to establish the name

of the tuple followed by an equal sign (which means ‘assignment’). After the

equal sign you start naming the elements included in the list. These elements

are nested inside parenthesis () and separated by commas. If the element being

established is a string, it needs to be between quotation marks.

For

printing the whole tuple you type the command print() and between the parenthesis

you type the name of the tuple. For printing just one element of the tuple you

type the command print() and between the parenthesis you type the name of the

tuple followed by the number of the element between square brackets.

NOTE: The

elements on a tuple are numbered starting from 0

For knowing

how many elements a tuple contains, you can use the command len(), between the

parenthesis you type the name of the tuple.

Also, you can add one tuple

to another and create a new tuple. For that, you need to type the name of the

tuple you are creating followed by an equal sign, followed by the name of the

first tuple and the addition sign followed by the second tuple you will adding.

Lists

A list is a

sequence of values that are nested into one function. These elements can be

strings, number, and even lists. You can have many types of elements within the

same list, for example:

Colors = [ ‘red’,

‘blue’, ’yellow’ ]

Numbers = [

1, 2, 3 ]

List = [ 4,

[5, 6]]

Other = [ ‘red’,

2, [5, 6] ]

As you can

see, for creating a list you need to establish the name on the list followed by

an equal sign (which means ‘assignment’). After the equal sign you start naming

the elements included in the list. These elements are nested inside square

brackets [] and separated by commas. If the element being established is a

string, it needs to be between quotation marks.

For

printing the whole list you type the command print() and between the

parenthesis you type the name of the list. For printing just one element of the

list you type the command print() and between the parenthesis you type the name

of the list followed by the number of the element between square brackets.

NOTE: The

elements on a list are numbered starting from 0

For knowing

how many elements a list contains, you can use the command len(), between the

parenthesis you type the name of the list.

Also, you can change an element on a list by

typing the name of the list followed by position of the element you want to

change between square brackets. After that, you place the equal sign followed

by the element you want to replace it with.

The Zen of Python

The Zen of Python is a document wrote by Tim Peters in August of 2004. This document stablishes 19 software principles that influenced the design of the Python Programming Language.

This principles are shown whenever you type the command “import this” on a Python interpreter.

viernes, 13 de noviembre de 2015

viernes, 30 de octubre de 2015

miércoles, 28 de octubre de 2015

Recursion

In some

programs we need to get a result that consists on repeating the same algorithm

certain amount of times. For obtaining the result we need to obtain the result

of the same problem in smaller instances.

For

example:

We want to

obtain the result of certain number raised to another number. This is the same

as multiplying the first number by itself during the second number of times.

But also,

this is the same as multiplying the first number times the first number raised

to second number minus 1.

For

example:

5^3 is the

same as:

5*5*5

Which is

the same as:

5*5^2 which

is the same as: 5*5*5^1 which is the same as 5*5*5*5^1

Now we just

need to know what 5^1 is equal to.

What we

just did is what we call recursion. We want to obtain the result of a problem

by solving the same problem in smaller instances. It can be applied to code in

this way:

And it

gives us the same answer:

Another

example is a number in the Fibonacci series.

This series

start with the value “0”, followed by “1”. After that, every number is equal to

the sum of the two previous numbers. This means that the third number will be

equal to 0+1 which is 1. And the fourth number will be 1+1 which is 2.

This can be

solved used recursion.

If we get

asked for the tenth number in the Fibonacci series, this will be the sum of the

ninth and the eight numbers.

And the ninth

number is the sum of the eight and the seventh.

The eight

is the sum of the seventh and the sixth…

And so on

until we get to the first two number, that are the ones that we actually know.

Here is the

series so you can prove the answer is correct

( 0, 1, 1, 2,

3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 )

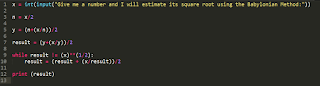

Loops with While

A “loop” is

how we call a process that repeats itself as long as some condition is true. As

soon as this condition becomes false, the process continues as the loop is

being left behind.

We state this

condition by the usage of the word “while” followed by the condition that needs

to be true in order to initialize the loop.

For

example:

As you can

see, the condition is followed by “:”. This is the only way for the computer to

know which is the condition that needs to be true in order to continue with the

loop. The condition will always be the

one between the word “while” and “:”.

The

evaluation “!=” means “ is not ” and “==” means “is”.

The

previous conditions which is “x != 0” means “x is not 0”. But if we had “x==0”

it would mean “x is 0”.

We can also

use “<” (smaller than), “>” (greater than), “<=” (lower or equal to)

and “>=” (greater or equal to).

The actions

being done inside the loop will be held in the following lines. These need to

be intended to be considered as part of the loop.

What this

program does is that is asks the user for a number, this number is stored in

two diferent variables which are “x” and “x2”. The first one will remain the

same and the second one will be altered during the loop.

If the

value given by the user is not 0, then the program will enter the loop.

In this

loop, “x2” will be altered until it becomes “0”. The number of times this

variable is being changed will be determined by the variable “count”.

The next

line is not intended, which means is not part of the loop. Therefore, this

action will take place once “x2” is 0 (which is the condition that breaks the

loop).

In the end, what this program does is to

determine how far from 0 is the number the user gave. After that, it prints the

equation that need to be done to this number in order to turn it into 0.

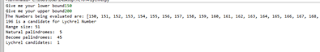

Another

example more complicated than the one stated before ca be this one:

In this

program, the computer chooses a random number between 0 and 100 and it asks the

user to guess it. The user has an unlimited number of tries to guess the

number.

The loop

initializes when the number given by the user is not the same as chosen by the

computer and it finishes once the user guesses the number. During the loop,

there is a variable called “count” that will count how many times the loop is

repeated; which is the same number of tries the user had.

Creating and Calling Functions

A function

is a piece of code that has been written some time before it is being used.

Some of these already come with python just as the case of the “Random”

function that has been used in the following example:

These

functions can be created by the programmer in the same code in which he/she

will be using it.

To create a

function we need to start defining it. To define it we write “def” followed by

the name of the function and the parameters that will be used in this between parentheses.

The next

line of code needs to be indented as this is what the function is supposed to

do. This function will print the primary colors:

If we try

to run this program, this is what will happen:

As you can

see, this program does not print anything. The reason for this is that we have successfully

created a function; however, we never called it. So this program knows that it

has to print “Red, Blue and Yellow” at some point, it just doesn´t know when.

So we need

when we want the function to be called. In this case the function will be

called if the following condition is true:

Note that the

line in which we state the condition is not intended. This means that this like

and what is followed by it is no longer part of the function we called “Colors”.

In this

program, the user is asked if he/she wants to know which are the primary colors

and it receives an input in the form of a string. If the string it received is “yes”,

then the function is called. This is what will happen if the conditions stated

below are true:

This is another

example of a created function. This function has an argument called “x”. This

argument is the name of a person. The function outputs the text “My name is”

followed by the value given to "x".

Before

calling the function we need to define what will be the value of “x”. After

that, we call the function by typing the name of the function followed by

parentheses.

After running it, this is what will happen:

We can also

change what the function will print by changing what is being witten between

the parentheses. For example, if instead of typing “name(x)” we type “name(x*4)”.

The

argument this function will be taking as “x” is not “Frida”; it is “Frida”*4,

which is “FridaFridaFridaFrida”. This is what will happen:

Another way

to create a function is the one shown below:

The

variable “stars” was defined inside the function; however, it can only be used

inside the function. For printing variables that were defined inside the

function we need to type “return” followed by the name of the variable at the

end of the function.

This way,

the program can use the variable correctly even if it is inside a function:

As you can

see, this program asks the user for a number, then it print the same quantity

of “*” that the user stated.

If we

decide to omit the “return” part, the result will be totally different:

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)